Film making has been in my family since the mid 1890’s, when my great-uncle Alfred was a pioneer of early film and cinema in England, Europe and, notably, Denmark. More about him in a moment.

My father spent most of his working life in the movie industry as an Editor and Live-Animator working post-WW2 on films for the Ministry of Information, then on commercial advertising, moving into feature films such as ‘The Plank’ and ‘The Battle of Britain’. My brother too joined the movie industry, as an animator, working on films like ‘The Yellow Submarine’, Pink Floyd’s ‘The Wall’, and ‘Watership Down’.

In 1952 great-uncle Alfred made a rare visit to England to catch up with his family and I remember, as a small boy, his coming to our house. My father borrowed a tape recorder, and recorded a long discussion with him about his early years and the development of film-making and the cinema around the turn of the 20th Century. He also made copious notes and, being a prolific documenter, produced a typed manuscript for posterity (I don’t think he had any intention of publishing it outside of the family circle). In 1982, he added some postscripts to round off the story.

In 2003 my father passed away, and amongst his effects the manuscript came to light. Using a scanner and Optical Character Recognition software, my brother and I have been able to rescue this ageing document as a soft copy. Far from being a record of family-based reminiscence, it is a fascinating study of the life of a ‘showman’ (that is how they were referred to at the time), and could be seen to be of some historical importance. I had considered placing the text on this website, but it would consume too many pages, so I decided rather to make it available as a PDF for those that are interested.

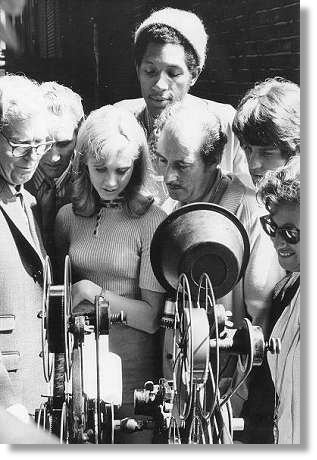

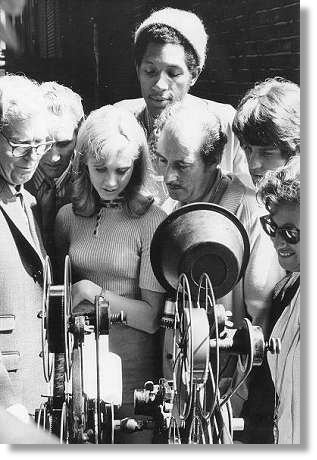

My father (left) with Olivia Newton-John and

Val Guest on the set of ‘Toomorrow’ (1970)

You can find it HERE. The text is exactly as my father wrote it - no attempt has been made to edit it in any way. Unfortunately we have not yet come across the illustrations he refers to.

For those that could afford it, home movie-making became a reality in the early 1920’s with the introduction, by the French company Pathé, of 9.5mm cameras, projectors and film. The film stock was initially B/W and was supplied in magazines containing 30 feet, which lasted about 4 mins.

If you had deeper pockets, then you could invest in the 16mm system which was introduced by Eastman-Kodak at about the same time - as a low-cost alternative to the established professional 35mm format. This produced higher quality images and eventually offered colour, but the cameras and projectors were more bulky and expensive to buy and run and not really intended for the home user, other than amateur enthusiasts. (This format still exists today, but is mainly confined to a few commercial and professional film makers).

In the mid 30’s Eastman-Kodak introduced the Standard 8 format, supported by cameras and projectors produced by a number of different manufacturers. This format was intended for the home user mass market, and used re-perforated 16mm stock which was exposed twice in the camera by inverting the reels after the first pass (each pass only using half the width of the film). After processing, the film was slit down the middle and spliced together to form a continuous 8mm strip. Each reel lasted about 3-4 mins. This format proved to be very popular, and marked the beginning of the home movie-making hobby revolution.

In 1965 the Super-8mm format was released. This was still 8mm wide, but used different perforations that allowed the frame size to be bigger, and thus improve quality. The film was already 8mm wide, and no longer needed two-passes and slitting after processing, and was supplied in a cassette containing its own gate-pressure plate for ease of loading. Advances in plastic moulding techniques enabled the production of budget-priced cameras, and there were affordable projectors developed that handled both 8mm formats. With the availability of Kodachrome colour film right from the start, home movie making now became an attractive proposition for everyone, even those who professed to be technically-challenged.

The mid to late 70’s saw a step-change in moving image recording with the introduction of Betamax, then VHS, analogue video-tape recorders. By the early ‘80s, many homes had one of these to play commercial movie tapes, and make off-air recordings. Within a couple of years portable versions became available with separate cameras to enable personal home video recordings to be made. By the mid ‘80s the cameras and recorders were combined together and the term ‘camcorder’ was born. Initially these were large machines which had to be shoulder-mounted but new formats were developed using smaller tape cassettes that enabled the camcorder to be hand-held. These formats were 8mm and VHS-C, which were eventually superceded by higher resolution formats Hi8 and SVHS-C which also gave improved sound quality.

Technology moved on and, in the mid ‘90s digital tape recording was introduced into the consumer market in the form of miniDV and Digital8 formats. This gave a significant improvement in resolution, and lower image noise, as well as HiFi stereo sound. Image sensors had also improved by now, and camcorders had a much better low-light capability - some even allowed infra-red recording in virtually zero light, useful for surveillance and recording nature.

Tape-based camcorders were not, however, destined to last for ever. By 2002 they had been largely superceded by tape-less models based on DVD, hard-disk, or flash memory-card storage. This meant the machines were smaller, lighter, and had increased battery life. Another difference was that the video content was stored in a file-based manner - each scene being contained in its own file (usually mpeg2, mov, or avi), which could be easily and quickly transferred to a mass storage device such as the hard drive of a PC. No longer did a 1 hour (say) video take 1 hour to transfer. Recent enhancements include the introduction of a High Definition (HD) specification. Camcorders that support it typically save their files in mp4 or AVCHD format.

Nowadays, video recording is not uniquely confined to camcorders - it is commonly available in mobile phones, tablets, and digital still cameras. Some of these even support full HD. I have a compact digital camera that produces full HD footage that far exceeds the quality I used to get from my digital-tape camcorder - and it slips into a shirt pocket!

This has been a brief history of the evolution of home moviemaking. It spans over 3 generations of family life, and has enabled unique personal records to be made of past family history. My brother and I, for example, have inherited a large archive of 9.5mm and 8mm family films from our father, which we intend soon to capture on DVD for ourselves and future generations to enjoy.

Unlike in the era of film, video (both analogue and digital) can produce a vast quantity of footage due to its almost limitless scene lengths. Relaxation in camera-operator disciplines can also mean that much of this footage is often unnecessary or of little interest. It has become essential therefore that some form of editing is employed to create an interesting and watchable movie. I devote a page to Video Editing HERE.

The success of a good movie lies in the quality of the camera-work. I was bought up in a movie-making household, and my father taught me from an early age a few simple rules of cinematography, and I have learned a few things myself over the years too, some of which I thought I would share with you here.

- Keep the camera still or, if you have to move it, do it slowly (unless you are tracking something, or there is a compelling reason to suddenly change subjects).

- Don’t overdo the use of zoom. If you feel the need for zoom, do it slowly, and don’t keep zooming in and out. If there is some action in the distance, then zoom into it first, before starting the scene, dwell on this, and then slowly zoom out if you need to put the action in context with the surroundings. In this way, the auto-focus will track better.

- While recording, keep your ears and eyes open to your surroundings just in case there is something that you need to pick up on nearby. This particularly relates to any interesting local conversation or announcements that may be picked up by the camera. Try not to cut off such an audible event mid-stream (unless it is embarrassing or defamatory).

- When panning, do it slowly. The general rule is to go at half the speed that you intended. Before panning, dwell on the scene for a couple of seconds, the same at the end. If you have time to do it, rehearse the shot first - to anticipate any problems.

- Look out for useful cut-away shots that you can take, which would be useful when editing.

- When travelling, try to capture appropriate place-name signs and entrances to events.

- Continuity - think, whilst videoing, of how you are going to edit this movie and transition from scene to scene, or place to place. If you take a train ride during the day for example, video the train arriving, and include some video inside the carriage while you are travelling. Try to avoid large gaps in time between shots, where a sudden difference in subject matter may be hard to explain or cover up when editing.

- Do not make scenes too short. About 10 seconds minimum is a good rule.

- Do not cut scenes off too early. Wait for a lull, or a natural break point.

- Avoid shooting into the sun. The subject will be in deep shadow, and the camera’s auto-exposure may even turn your subject into a silhouette.

- When children are the subjects, lower the camera to their level.

- If you are capturing street carnivals or parades, do not cross over to the other side of the road for a different view - the result will look like the event is suddenly travelling in the opposite direction.

- If you are walking with a group, try to run ahead to get them walking toward and past you. This is so much better than constantly capturing their backs.

- People, not places. When on family or group holidays it is tempting to concentrate on creating a travelogue of places and capturing local interest. This rarely stands the test of time however. At least 60% of your time your camera should be pointed towards your family or group, preferably with some local interest in the background. Avoid constant repetition of mealtimes.

- Do not be tempted to use any effects/fades/titles available in your camera. These are best performed later using an editor.